by Wendy Clupper

Since before 1980 performance artist Tim Miller has been exploring, engaging, and disrupting the lines between religion, politics, and sexuality. As one of the founders of P.S. 122 in New York City and as one of the NEA Four, Miller has taken on the religious right and conservative governments, and fought to draw attention to divisive issues, specifically sex and the Church.

Since before 1980 performance artist Tim Miller has been exploring, engaging, and disrupting the lines between religion, politics, and sexuality. As one of the founders of P.S. 122 in New York City and as one of the NEA Four, Miller has taken on the religious right and conservative governments, and fought to draw attention to divisive issues, specifically sex and the Church.

But he has also worked tirelessly through his writings and performances to both show and teach others how telling one’s own story of struggle and survival can better our world. He tours performance pieces all over the United States, and leads unique performance workshops at universities and performing arts centers across the country. For not only has Miller performed sermons in Anglican churches, he has embraced those very communities, having himself come from a religious background. These truths complicate his art, which some decry as blasphemous and others celebrate.

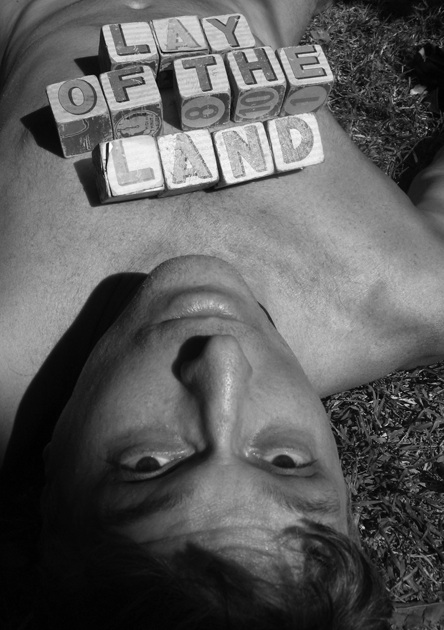

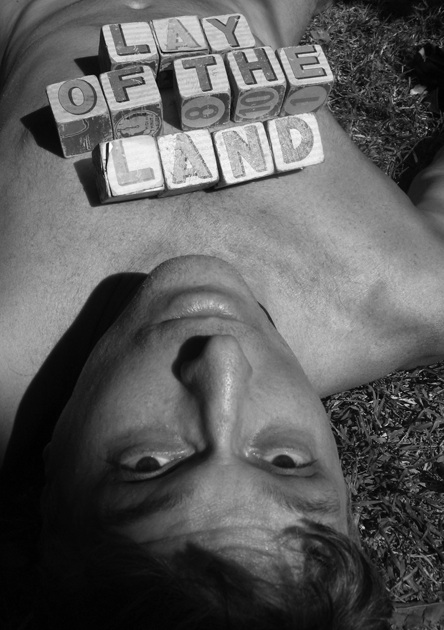

His latest piece, Lay of the Land, focuses on growing up a gay boy in a conservative evangelical California family where boys were given guns as a rite of passage, considers the current trajectory of political hate that continues to block marriage equality for gays, and touches on Biblical analogies to punctuate the modern dilemma facing gays today. Miller has proven himself to be fearless when it comes to telling his own story, pulling from any and all cultural tropes he believes will illuminate his unyielding drive to speak out and fight issues of censorship, hate, inequality, and intolerance.

In the fall of 2009, Wendy Clupper participated in one of Tim’s performance workshops. Tim, Wendy, and fourteen others spent a week playing and creating both group and solo works, which we premiered at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco. It was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to work closely with an artist who sees the creative play space as sacred, and sacred spaces, like churches, as stages for deep self-expression.

In 2010, having had several months to reflect on our workshop, WEndy spoke at length with Tim and asked him to clarify and amplify his feelings on some of the tenets central to his approach to creating, promoting, and encouraging performances that shake up the social boundaries between the personal and the public, as well as the sexual and the spiritual. That interview follows.

Wendy Clupper: Tim, how would you categorize your staging of spirituality in performance versus your performance writing that addresses the spiritual?

Tim Miller: Any performance event has, like a church gathering, energy, expectation, politics, style, erotics. That is what is in a fundamental space in the way I am using it, as my own space—especially with solo performance. It is where my homosexual story is told, which in my case, parables the things I want to bring forward and present in the performance. It is there, in my wiring. Certainly more people can be reached that way, whereas sometimes through that kind of performing you can reach so many more venues. But I can think of lots of ways for a performance to live—for instance, YouTube performances. Now it’s almost like, some boy in West Texas can actually find that performance and transcribe my work, and perform it himself. Ideas and energy and personality, it passes from person to person.

In my essay, Jesus and The Queer Performance Artist, I write about that, and it is an essay I am proud of as one of the few queer lefty performative types who address religious traditions, and has over many years, with sermons and teaching series. When I go to a Baptist college, I am actually able to engage. It is not a strange space to me. I go and speak at churches, and it’s a key space in a country as wildly religious as this one, the only religious Western country at this point deeply steeped in politics, where ninety percent of people believe in God. We are an anomaly. And anyway, it’s important to engage either in person or in writing. And the church stuff is only the steeple. What that engages is a diversity discourse and what are the fundamental building blocks: race, ethnicity, and religion.

WC: What else goes into your thinking about making performance?

TM: The other crucial things then are: culture, comfort, and community, which all happen more in a live performance than in a one-on-one way, as in someone reading my book. But then, even more so in a workshop, where we start out holding hands. And actually, the pieces that are made in workshops are little spiritual political essays: “How do I make sense of the world? How do I dress?” If we looked at it as not the only thing that the piece addresses but of how the work got created in the space, and recognize each others’ humanity, then we see how performances can question the big stuff.

I was thinking of the performance piece you created in our workshop, Wendy, where you were talking about fixing a tomato plant, that was your story—and such are the materials we work with in a piece. Identity, family, nature—such rich prayerful spell-casting. And prayerful space is also a spell-casting space where we are gathering our energies, gathering a message, a metaphor. That’s core to the work we do with each other, and to do basically the same process in a stained glass sanctuary is a great space to work that out in.

WC: But in your performance you also address hot political issues like marriage equality.

TM: In some ways. I’ve never thought to say this, but my early work was more “surface trangressive.” However, my work was always political from the beginning. Making pieces about relationships is at the heart of my politics. And that’s what I was thinking about performing. I wasn’t thinking about the states that are free for gays to marry or that are hate states, like Iowa versus New York. Back then, I didn’t have that level of rhetoric, because it wasn’t our reality then. These are the constants we live through: sexuality, love, relationships. In the last fourteen years, since the Hawaii thing1 the way love connections and sexual partnering happen, reality then collides with the insanity of American politics.

Now, we’re engaging in a state-by-state duking it out from one state to the next, just as Maine took away its equality from gay citizens or Florida’s laws against gays are right out of the Third Reich. Gay people can’t be equal there. It’s insane and extreme. Now, it’s not poetics or narrative, it’s how that material exists in the world in complex legal ways. It’s hitting us hard just now but there has been a very strong through-line. Also, I’m more married now than I have ever been in my life and for me, that adds to the heat of it.

When I was still in high school, fourteen years old and on a field trip, we drove by a church where a gay wedding was happening. And so the mainstream battling for this has been going on for thirty-five years because of the Supreme Court. And I have been performing throughout this whole era asking: What do we do? How do we acknowledge people in our community? Another way I engage these mainstream religious denominations, like the United Church of Christ, is to have the conversation. And I have done the heavy-lifting before it was on the screen or even a part yet of my creative response. I remember when they were fighting about what many were saying which was, “I can’t remain a minster if I can’t marry gay congregants.” And there was more visible hideous hate mongering. But it got going because fair-minded people in Judaism and Protestantism got this topic on our national discourse.

WC: Explain something to me about what drives and challenges you in your work.

TM: Iowa, where I know you are from, and where gay marriage is legal, is swirling in my head today, along with thinking about gun control, which we might think are far apart—but it’s not such a leap. I am interested in the giant cultural materials: Religion, guns, politics; they are the big markers. Especially for me, I am drawn to things that I imagine I don’t have a place to speak from as much as when I was a performance artist doing sermons, where all of that new stuff in the cultural debates was happening when I was serving communion at an Anglican church. I am interested in connecting my queer art to those places.

I was raised hunting and shooting. What is wrong in our society, which is not much of a debate, is that those who hate us, who would use guns to kill us, hold all the cards and it’s another important space for me to relate to in my work. One of my frustrations is that we have spent more than thirty years on this topic of equality and there are so many subjects I am interested in but marriage equality is an important thing I will continue to address in my work.

And going back to guns, they are a powerful totem considering the harsh social discourse we are engaged in. Consider that in this, my lifetime on Earth, I have participated in this tradition. My .22 caliber that I got when I was seven years old was because of a family tradition that says that as a boy grows up he gets a bigger gun. Now, I grew up in suburban Los Angeles but it’s a big part of American culture everywhere. One of the problematic things that make up the culture of America as well. God, marriage, guns…what’s next? Those powerfully charged spaces are important to me. It’s what I was talking about in the performance writing I did today. And it’s something that has kept my interest throughout my performing, the larger picture I’m engaged in, the race/gun/sex/queer stuff. This is a job for performance art. These are the things we should be taking up, looking at, engaging. Certainly the work I’ve done is not just about “lower-case religion” but also shows my interest in the shamanic. I am interested in taking on all of my received cultural materials and I’ll be back at my church this weekend interested as ever and cognizant of how much it is a powerful space for me to engage with and within.

WC: Can you talk about your latest show you have toured all over the country, Lay of the Land? Where did the inspiration for the work come from?

TM: In some ways, that show, it’s right on with what you and I are discussing. The core material of that piece is that I was working in small performance space and working with artists in Chicago, and in this period, I started to follow my nose and create a piece about what had been happening with Proposition 8 passing and working within the community of the church. And these amazing artists were there at this core moment when I remembered the day my father almost slit my throat to relieve my windpipe from the meat that was lodged inside. Now you know, I am always ready to go right to the giant cultural materials and the formative elements of culture for my artistic inspiration.

So, I began to think about the crazy wild nature of that narrative of God telling Abraham to kill his son. So then I thought about what is going on with homophobia and racism in America and how that plays out. And how much mayhem and murder are we ready to enact. And the whole piece leapt out of a purely intuitive place inside me about being a queer boy choking on a piece of meat after coming home from Sunday school, and the week before hearing the story of Abraham. And the heart of the piece comes from a place with humor and kink and that analogous story. I start with this core event; I am trying to say that to cut Isaac’s throat is symbolic of what is going on in the world now. That symbolism is the kind of electric socket as a performance artist or writer you want to throw your work into.

WC: Can you make a distinction between a sermon versus a performance?

TM: It’s a continuum. But you can ask more of a performance audience of their participation than you can at a large parish, though something different is happening. They (the audience) are powerful mirrors for each other. In Western cultural materials you find that through religious practice all practices are bound up with each other. Now, I perform in parish halls.

Morality plays from early history were a story-telling tradition with themes and narratives and magical materials of a culture. They are so connected with each other. And in that sense, space and architecture is the same. But it’s also a question: What can you and can’t you do in a church?

WC: Tell me about your moral compass as an artist.

TM: Being in the art world as a young artist, the early 1980s, there was a signal I received that creating political text, writing agitprop performance, teaching and writing sermons, was a way of making domestic homosexual expression a reality. Artists are supposed to express, not fear it, or be fixed or frozen by it. To me, it is powerful and rich voice to claim. I trouble it in my performance, always. I think that use of that urgency and the stuff we need to engage, happened when what changed at the time and was this enormous spiritual challenge, was the AIDS crisis. It was a big lesson in urgency and mortality, and it gave wind to my sails that we didn’t ignore what was happening. I’m not dead and so many of my friends are and were then facing death and loss. They are dead now for twenty-five to thirty years. That is so giant to absorb.

And now we need to do work with ACT UP and marriage equality and immigration. We have a short time, so let’s push the boundaries, push sexual context. My work is accessible to anyone, for instance, when I’m doing a show in North Carolina live, talking about double-fisting, and doing work about sex and cum and queer visibility for a Republican, home-schooled Southerner in a position of authority. It is quite remarkable what’s going on in those performance spaces, which is where I perform. I perform and travel all over the country in those kinds of spaces. And it’s the thrill of pushing all those buttons, showing how deeply connected I am as an American to our culture that includes religion, firearms, as well as a history, and then linking it to queer citizenship—that is very important to me.

I think I would be not fluent and comfortable being able to negotiate these issues as an artist if I didn’t know that I can use the materials of culture and go into spaces that are religious, conservative, and anti-gay. I see that kids are more religious today than when I was a kid. Nowadays, kids are so much more conservative than when I was growing up and we are living now in a so much more conservative world than we did then. But you can’t negotiate those spaces without addressing those issues within them.

Now, when I am performing in Alabama, it’s the same conservativism at Chico State. Those are extremely conservative parts of the country to negotiate theses spaces and not freak out. Good cultural fluency as an American artist in a religious country means you ignore it at your peril. There are a wide diversity of performance spaces in such regions for me to address these issues, especially since gay people are constantly the scapegoat in a certain kind of religious rhetoric.

WC: How then are you able to map what is both in your heart and at the heart of your writing and solo performing?

TM: First, I want to acknowledge how deeply entrenched in Western culture we are. You inherit Western cultural religious materials, even if you’re not religious. You still have the cultural practice woven into every aspect of being in this culture. I have cultural practice to mark that for me. And I am holding and taking it on, but then I don’t have a negative relationship with my religous upbringing. I was raised in the coolest of the Protestant mainline Christian denominations, the United Church of Christ (UCC), the only ones that will marry gay people in churches of all of the big canonical religious traditional denominations in America.

I acknowledge how those religious materials are woven into my politics, my mission. And I have to consider how do the words mean as much as what’s my artist’s vocation and mission? What are the words I am using that are used for spiritual practices? The linkages of these lines are so intimate it seems to me, it is extremely rich and I need to want some of that and to see what is there. I can’t imagine not doing that and not in an ongoing way. I will walk into a parish hall in Nebraska to talk to other parishioners after church. It’s a familiar place for me and interesting to be in a place where we should be able to go into and communicate. Churches and performance spaces, I have done work in both, such as my performance space in Santa Monica, Highways Performance Space, or P.S. 122 in New York City. P.S. 122 even feels like a church. It has this stained glass window there with a great message on it: Every waking hour we weave, whether we will or no, Every trivial act or word into the warp must go. Now P.S.122 is the main center for contemporary performance in the United States, and I co-founded it thirty years ago. So, I feel them both as churches and see people relate to them as churches. People attend them in the way that art/church thing happens.

WC: Would you say that your work as a contemporary performance artist has addressed religion more than anyone else?

TM: Not really. Annie Sprinkle’s work does. She is of course, in San Francisco, which is a charged space for these issues. But hers relates most strongly to my own work. No, I feel like I’m in close kinship with a lot of people as artists. Annie and her partner Beth have the whole eco-spiritual thing linked to feminism and Gaia worship and a rich set of feminist relationships to nature in terms of performance that is highly spiritual in its practice. That work is deeply charged with erotics, where audience and ritual are in very good company.

WC: Returning to your essay “Jesus and the Queer Performance Artist,” you say that Jesus was the first man you ever loved. But you also talk about how you emulate who he was. Do you ever think of yourself as both activist and savior, say for giving a voice to those who have been silenced?

TM: Well, I think of it as I am trying to be secure in a country where nothing ever changes and the sanity of our reactionaries gets more poisoned by the day. You certainly have to appreciate progressive social change with the idea that you won’t live to see it happen. I know that I won’t live to see America not poisoned by homophobia beyond us living. Obama is the beginning of an enormous amount of racism, a new era of racism.

There is something I think about a lot that the early American feminist leaders expressed about the work in our own lifetimes not being for ourselves alone, and these women knowing that the work they were doing was not necessarily going to benefit their daughters or their granddaughters but might it might benefit their great-granddaughters. These women called it right. I’m thinking about the original document of American feminism, The Declaration of Sentiments and what these women were fighting for then. They knew that you are well served to keep in mind that in all the work you do, to not assume it will create change in your lifetime.

If anyone would have told me as a child that this country would be frozen in bigotry today, I would not have believed them, that we would be living in a religious dictatorship. I would never have believed we would be so backward at this time. Now, consider gay rights and the legalization of gay marriage. Not one single bill exists. There is nothing. We haven’t seen anything. Some have gotten written but not gotten in. Never a piece of gay legislation. Small bills. And maybe that’s disheartening but you have to take that long view increasingly.

WC: Considering all of the performances you have created throughout your career, what remains precious and important to you about reaching people now or in the future?

TM: Consider the place you and I did the performance workshop together, San Francisco, it is chock-full of change-agents—but within that group, we met people who still needed to tell their story and become empowered as artists. What’s important is when I am in the middle of nowhere—that I can reach some queer boy, or sometimes it’s the straight girl who becomes the one excited, transformed, emboldened. That feels like the most purposeful thing I know I can do right now. Every newly engaged gay person ready to speak the truth and to seek change can help us imagine a more just world. And it is a great thing to launch our story and message of hope for change out into the world to people who will be here long after I’m gone. That feels incredibly important—along with that depressing sentiment that those fighting for equality aren’t likely to see change in their own lives, but it is honest and true. It’s not the work of one lifetime but many lifetimes and generations and connections.

Notes

1. Since 1993, Hawaii has refused to grant acceptance of legislation allowing same-sex marriages and civil unions. This summer, the Governor vetoed the latest bill that would have allowed for civil unions, continuing the state’s on-going debates over gay equality.